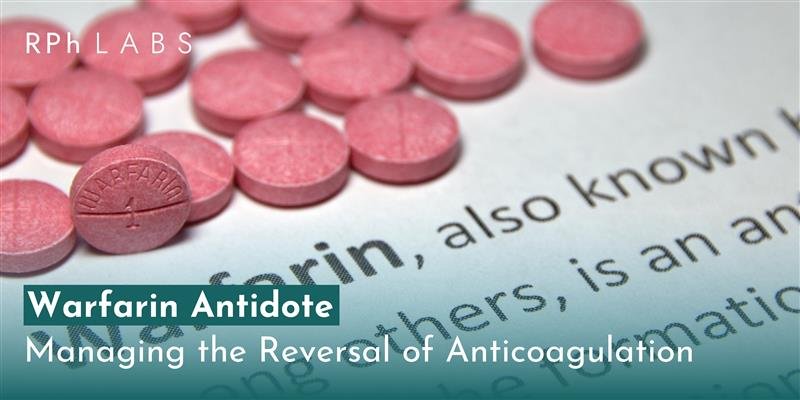

Warfarin Antidote: Managing the Reversal of Anticoagulation

Warfarin has been one of the most frequently prescribed oral anticoagulants for treating various conditions brought about by blood clotting disorders for decades. It is used to treat atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, and the prevention of stroke in heart disease sufferers. Though highly effective at preventing blood clots, warfarin has the potential to increase the risk of bleeding significantly. The risk increases either in the event of an overdose or due to interaction with other drugs or factors that alter its metabolism. As such, an antidote for reversing warfarin is essential and would sometimes be called for.

This article includes some warfarin antidotes and their mechanisms, along with mechanisms and applications in clinical practice.

Warfarin’s Mechanism of Action

Before knowing the warfarin antidote, understanding warfarin’s mechanism is critical. Warfarin is a Vitamin K antagonist. It inhibits clotting factor synthesis. Vitamin K is essential in clotting factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X. Vitamin K epoxide reductase is the enzyme that warfarin impeded from converting Vitamin K into its active form. Without active Vitamin K, the liver could not make clotting factors successfully; therefore, clot formation could not be achieved.

The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is measured by the International Normalized Ratio (INR), which measures blood clotting time. Therapeutic INR is usually set between 2.0 and 3.0, depending on the patient’s condition; however, if the INR becomes too high, dangerous bleeding complications may occur, and the effects of warfarin are reversed.

Antidote for Warfarin

Several antidote for warfarin exists to reverse the anticoagulant effects. These warfarin antidotes work by different mechanisms and are used in various clinical situations based on the severity of the overdose or urgency of the problem.

Vitamin K (Phytomenadione)

The main antidote for warfarin overdose is Vitamin K. The direct treatment against warfarin effects allows replenishment to take place via replenishing an active supply in the body with Vitamin K, thereby allowing the liver function to commence production of clotting factors back into the bloodstream, which could then clot the blood.

- Oral Vitamin K: In mild to moderate warfarin overdose (slightly elevated INR, but no active bleeding), oral Vitamin K may be enough. This treatment can take several hours to have an effect since it requires time for the body to produce new clotting factors.

- Intravenous (IV) Vitamin K: Intravenous is a much more serious overdose, or where rapid reversal is required (in the presence of significant bleeding or high levels of INR), then intravenous Vitamin K is favored as treatment. However, rapid infusion in high doses of IV Vitamin K can be associated with allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, so care must be exercised to slow the infusion.

- Dosing: The ideal dose of Vitamin K depends on the level of elevation of INR. A minor increase in INR usually calls for an oral dose of 1-2 mg. Significant overdoses and major bleeding will require a maximum dose of up to 10 mg IV.

Prothrombin Complex Concentrates (PCCs)

Another option for reversing the effects of warfarin has been the use of prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), mostly in emergencies. These concentrations contain clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X, all of which are inhibited by warfarin. Their replenishment results in a quicker restoration of coagulation.

Advantages: These fast-acting agents can reverse warfarin’s anticoagulant effects within as little as 30 minutes post-administration, making them useful in severe, life-threatening bleeding cases where the agent needs to be reversed quickly.

- Activated PCC (aPCC): PCCs activate non-activated factors and contain active clotting factors. They are usually used, especially when acting fast is concerned, such as in patients with severe bleeding conditions.

- Non-activated PCC: These are packed with non-activated clotting factors. These are frequently used in the management of minor bleeding or prophylactically.

- Dosage: The PCC is generally given according to the patient’s weight and the INR value. The dosage commonly used varies from 25 to 50 units per kilogram of body weight.

Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP)

Another alternative for warfarin reversal is Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP), especially when PCCs are unavailable. FFP contains all the clotting factors necessary for coagulation, including those inhibited by warfarin. However, FFP requires careful handling and must be thawed before use, which can delay its administration.

- Limitations: FFP is less efficient than PCCs and takes longer to show results. It also carries the risk of volume overload, especially in elderly patients or those with heart failure.

- Dosing: The dose of FFP is generally 10-15 mL per kilogram of body weight. The exact amount may vary based on the severity of the bleeding and INR levels.

Recombinant Activated Factor VII (rFVIIa)

Recombinant activated Factor VII (rFVIIa) is another alternative used in some cases of severe bleeding. However, its use is less common due to its high cost and potential for side effects like thrombosis.

- Mechanism: rFVIIa works by activating the clotting cascade, thereby accelerating clot formation.

- Indications: It may be used when other reversal agents are unavailable or ineffective, especially in patients with severe bleeding or life-threatening situations.

Other Considerations in Warfarin Reversal

In addition to giving warfarin antidotes, clinicians will monitor patients during and after the reversal therapy with care. Following assessments of patients’ INR, clinical statuses, and indicators of bleeding appropriately ensures proper handling.

- INR Follow-Up: When administering Vitamin K or PCCs, further monitoring patients’ INRs helps determine adequate reversal and dictates additional treatment actions.

- Bleeding Risk: Although warfarin reversal is important in bleeding, the risk of over-clotting should be avoided since it can lead to thromboembolic complications. Therefore, clinicians must balance the need for reversal with the risk of reintroducing clotting.

Does Wellbutrin cause platelet abnormality?

Wellbutrin (bupropion) is seldom associated with thrombocytopenia but has been documented in a few cases of bleeding complications. Low risk, exercise caution when concurrently used with other drugs that inhibit bleeding or have an effect on platelet activity. Monitoring of patients with a bleeding disorder could be recommended. Learn more by clicking here: https://rphlabs.com/does-wellbutrin-cause-platelet-abnormality/

Bridging warfarin for prostate embolization

This group of patients will often require bridging therapy when they are being prepared for a procedure such as prostate embolization to avoid clotting with adequate anticoagulation. Because warfarin is stopped before the procedure to minimize bleeding risk, LMWH is frequently used as a “bridge” that maintains anticoagulation until warfarin therapy can be safely resumed post-procedure. To learn more about Bridging warfarin for prostate embolization, click here: https://rphlabs.com/bridging-warfarin-for-prostate-embolization/

The Role of PGx Testing in Warfarin Therapy and Antidote Management

The pharmacogenetic testing of RPh Labs is a crucial factor in optimizing warfarin therapy and the requirement for antidote interventions. Variations of enzymes, for instance, CYP2C9 and VKORC1, can alter the way an individual metabolizes warfarin and their sensitivity to the anticoagulant effects. PGx testing determines the individual’s risk factors, which are higher on either end-to-excessive bleeding due to slow metabolism or clotting due to fast metabolism on warfarin. This strategy would reduce exposure to antidotes such as Vitamin K and Prothrombin Complex Concentrates since INR levels could be prevented from becoming unnecessarily high by using genetic information for tailoring warfarin dosage.

Conclusion

Warfarin is a highly effective anticoagulant used to prevent and treat conditions related to abnormal blood clotting. Still, it carries a significant risk of bleeding, especially when INR levels become too high. The need for an antidote for warfarin becomes crucial in such situations. Vitamin K is still the first choice, but PCCs, FFP, and rFVIIa are also available depending on the urgency and severity of the case. PGx testing also aids in tailoring warfarin dosing, thus reducing the use of warfarin antidotes as the risk of bleeding or clotting is diminished. Anticoagulation for the procedure is sometimes bridged by medications such as low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) during treatments like prostate embolization. Careful management and monitoring will be necessary in balancing the risk of bleeding with the risk of thrombosis to ensure safe and effective therapy with warfarin.

FAQs

The major antidote to warfarin overdose is Vitamin K, which restores normal blood clotting by replenishing the body’s stores of active Vitamin K and allowing the liver to manufacture clotting factors.

Oral Vitamin K is slow to take effect because it gives the liver time to create new clotting factors. However, intravenous Vitamin K works more quickly, sometimes within hours, especially in emergencies with severe bleeding.

Indeed, some reversal agents, like intravenous Vitamin K, can cause an allergic reaction that can lead to anaphylaxis when infused too quickly. PCCs predispose patients to a higher chance of thromboembolic events. FFP carries the potential risk of volume overload in certain patients.

Bridging therapy uses a short-acting anticoagulant, including low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), to sustain anticoagulation when warfarin is withheld before procedures. This allows the patient to stay protected against clotting but minimizes the risks of bleeding during the procedure.

Leave a Reply